Heung | 흥 Coalition

︎About 흥

︎Writings

︎Writing Group Workshop

︎Podcasts

︎ Twitter (X???)

︎ Instagram

︎About 흥

︎Writings

︎Writing Group Workshop

︎Podcasts

︎ Twitter (X???)

Feminism and Gender Beyond Borders and Oceans: A Dialogue Between Chicanx and Korean American Feminisms

February 20, 2021

By: Rachel Lim, Dinorah Contreras, and Cintli Cardenas

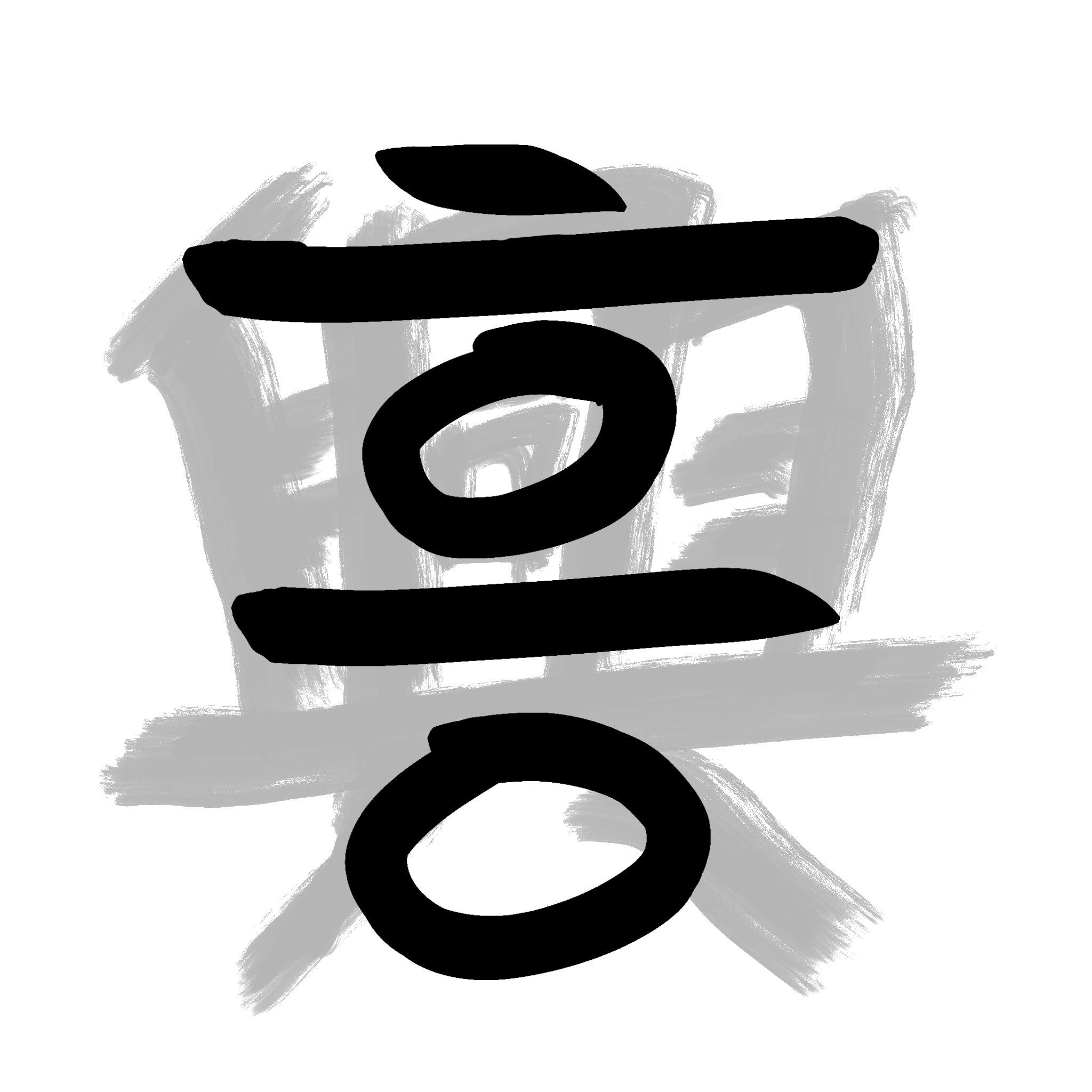

Protest in Mexico City against gender-based violence against of women after the murder of Ingrid Escamilla (February 2020) | Eyepix/NurPhoto/PA Images

This reflective essay is generated by a conversation entitled, “Feminismos transfronteristas: Diálogos sobre migraciones coreanas y chicanas,” hosted by the Círculo Mexicano de Estudios Coreanos (Mexican Circle of Korean Studies), and El Colegio de la Frontera Norte (Tijuana, México).

In 1979, Cherrie Moraga, a feminist Chicana writer, described “the necessity for dialogue” among feminists from different racial, ethnic, and national backgrounds. As a mixed-race lesbian woman, Moraga wrote compellingly about the “responsibility to her roots—both white and brown, Spanish and English-speaking.” Inflected by a sense of accountability as well as her belief in the possibilities of social transformation, Moraga pressed for dialogue, both for survival and for “real joy”—the transcendent possibilities of collective dreaming and intimate solidarity. “One voice is not enough, nor two,” Moraga writes, “although this is where dialogue begins.”

Following Moraga’s concept of dialogue, we bring our voices together at a crucial historical juncture for various feminisms across different contexts of ideology, space, and power to discuss the experiences of migrant women in cross-border contexts from a feminist perspective. In addition, the question of dialogue among women foregrounds the essential task of sharpening the lens of gender across networked global institutions and the everyday experiences of patriarchal power relations. In Mexico, for instance, #UnDíaSinNosotras (#ADayWithoutUs) catalyzed a nationwide strike by women protesting gender violence and the callous disregard of the current governmental administration. In South Korea, the establishment of the Women’s Party (여성의당) marked the foundation of South Korea’s first feminist political party. Both events happened on March 8th, International Women’s Day, which speaks to the broadening of transnational institutions that link the question of “woman” between different spaces across Asia and the Americas. At the same time, it is possible to see similar critiques—of pervasive cultural chauvinism, of bureaucratic enablement of gendered violence, of hostility toward sexual minorities—emerge from different social locations and struggles.

In this regard, we stage our dialogue across the circuits of Korean and Mexican diasporas, with special attention to cultural crossings of the U.S.- Mexico border. We do so because this conversation emerges from our specific positionalities as both researchers and individuals, as Korean American and Mexican women and scholars who study migration across an increasingly militarized U.S.- Mexico border as well as the transpacific and hemispheric borderlands between the United States, Mexico, and the Korean peninsula. In doing so, we are indebted to Chicanx and Asian American feminist movements that have shaped a broader understanding of the “triple oppression” of racialized migrant women from the patriarchal context of the society of origin, the patriarchy of the host society, and the subordination of migrant and class conditions. We have drawn from these shared understandings to think through questions of epistemology and method that have emerged from our experiences conducting ethnographic fieldwork among Korean migrants in Mexico.

Image credit: AFP

For Rachel Lim, this dialogue emerges from her specific positionality as a second-generation Korean American woman who researches Korean migration to and from Mexico. During her fieldwork in Mexico, Rachel constantly confronted the limitations of the insider/outsider dichotomy for migration research. She first came to know Koreans in Mexico through her maternal aunt and uncle, who lived in Managua, Nicaragua for ten years and then in Mérida (Yucatán), Mexico, an introduction that no doubt eased her access into the community. The process of conducting ethnographic research—relying on word-of-mouth information and informal chains of sociality and reciprocity—in some ways echoed the networks that Korean migrants utilize throughout the diaspora. Over the course of her fieldwork, beholden to the generosity of interlocutors, friends, and strangers, she was reminded that social status is often situational, as her own role constantly shifted in relation to perceptions of her age, nationality, gender, and level of education.

Living in Mexico challenged some of Rachel’s U.S.-centric assumptions regarding the relationship between ethnicity, race, and nationality. For example, referring to “Korean Mexicans” as the hyphenated correlation to “Korean Americans” imposed a U.S. model of racialized ethnic identity upon a context where such formations of subjectivity were not necessarily legible. Recent Korean migrants often insisted that they were “Korean” and not “Korean Mexican,” and the descendants of Korean migrants who arrived in the Yucatán peninsula in the early twentieth century distinguished between “los coreanos-coreanos” (Korean-Koreans) by calling themselves “Mexicans of Korean descent.” Hyphenated identity could conceal as much as it revealed, producing a fiction of undifferentiated diasporic subjectivity without attending to different histories of racialization and exclusion.

“Hyphenated identity could conceal as much as it revealed, producing a fiction of undifferentiated diasporic subjectivity without attending to different histories of racialization and exclusion.”

For Dinorah Contreras, her concern about addressing these issues lies in her approach to the study of religious Korean communities in Mexico, along with her academic training and field work in anthropology. In addition, there is her own experience as a migrant within different Mexicos: Guerrero, Mexico City, and Tijuana. These spaces are also inhabited by a diversity of Korean identities expressed in activities of all kinds—however, Dinorah has paid special attention to religious practices in Protestant churches in Tijuana and Mexico City, and one Catholic nuns’ congregation in Guerrero, a southern Mexican state.

In dialogue with Korean women who live in the aforementioned contexts, she states: “Even though our ethnic identity and mother tongue are different, I have been able to see that there are shared concerns between the Korean women who I had the opportunity to speak with and my own experience of inhabiting different Mexicos as a woman: the feeling of uprooting, fear of displacement in hostile and unknown urban Mexican spaces, loneliness, silence derived from language isolation, job uncertainty and, in some cases, the searching for answers to these inconveniences in the development of one's spirituality, and the link-building with the community.”

In the growing wave of studies on Korean migration in Mexico, Dinorah stresses the fact that there is still no solid gender nor feminist perspective that accounts for the conditions in which Korean women live, inhabit, and experience a diverse and complex country like Mexico in dialogue with their own personal and collective history. She noticed this lack of gender and feminist perspectives over the course of her research. The main reason for these lacunas might be that most studies about Korean migration in Mexico have been conducted by men.

In particular, women migrants’ experiences have not yet been recorded in spaces of academic dialogue, due to biases toward the so-called “neutral” view of migration that often invisibilizes the gender and sexuality condition of immigrants. Therefore, Dinorah's research seeks to question the traditional view that masculinizes Koreans in Mexico as highly skilled workers in South Korean companies, as businessmen or entrepreneurs, as merchants, professionals, male missionaries, priests, etc. and ignores the role of the migrant’s female “companion” who is turned into a shadow, a category which encompasses a great diversity of women: highly skilled working women, housewives, Protestant missionaries and Catholic nuns who work closely with Indigenous and vulnerable communities in southern Mexico, Korean language or art teachers, interpreters, students, and professionals. In her case, these thoughts had been waiting in her field journals to be shared.

For Cintli Cardenas, living in South Korea a few years ago as a graduate student doing research on the adaptation experiences of Mexican female marriage migrants residing in the ROK motivated her to be part of this conversation. With regards to her personal experiences with migration, she does not recall feeling like a “migrant” in general (that is, in terms of national identity, belonging, displacement and the feeling of no-return) as she went back to Mexico once her studies finished. However, she felt like a part of the ethnic minorities in the country and went through processes of adaptation to other cultures, languages, weather, food, and ways of interacting with people, as Seoul and the university she attended constituted cosmopolitan spaces in which a diverse range of nationalities and identities intersected.

For Cintli, it is important to recognize that migrant women share common struggles, difficulties, challenges, feelings, and experiences in host societies that do not recognize them as “theirs.” In difficult environments where identity construction and belonging are not granted for migrant women, it is crucial to visualize their struggles and give voice to their testimonies in the way proposed by Cherrie Moraga.

As Moraga has argued, relationships between women of diverse origins and different sexual orientations have been fragile at best. However, from her point of view, to build a true alliance it is necessary to understand and assimilate the experience of oppression from our own personal stories—the imperative to remember that we are each situated at the particular intersections of power and domination. Only in this way will we come to stand in solidarity with those whose lives are shaped by axes of power that differ from ours.

“…to build a true alliance it is necessary to understand and assimilate the experience of oppression from our own personal stories—the imperative to remember that we are each situated at the particular intersections of power and domination. Only in this way will we come to stand in solidarity with those whose lives are shaped by axes of power that differ from ours.”

Four decades after Moraga’s work, in the era of global connections offered by the virtual world, it is easier to be aware of the situation in which many women live globally. But theoretical knowledge, Moraga warns us, is not enough: one of the dangers to which we expose ourselves is believing that we can face shared oppression in purely theoretical terms, leaving aside the "emotional wrapping in the heart.” But if we understand the border as a space for meeting and mutual knowledge, we will truly be able to strengthen the links resulting from our particular conditions. By writing together, we seek a way to see the border as inhabited. From the perspective of Christine J. Hong, it is in this space of liminality where migration is experienced, the feeling of in-between—that is, from being in the middle, but it is also precisely from here where opportunities emerge for the constitution of new migrant women identities (in resistance).

Drawing from our shared reflection, we conclude that one way to establish dialogue among migrant women is by centering creative expression. In this sense, literature, poetry, and other texts that include testimonies of migrant women can become a common space of dialogue and understanding, as a bridge between and among distinct but shared struggles that represent borders and otherness, such as class, gender, language, ethnicity, body, and nation. In other words, the close reading of literary products authored by migrant women (Chela Sandoval, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Gloria Anzaldúa, and Sonia Saldívar-Hull) can prove to be a useful method to visibilize gendered testimonies of migration that resonate across subjectivities of race, class, sexuality, and nationality.

For example, bringing together the voices of Chicana writer Gloria Anzaldúa and diasporic Korean writer Don Mee Choi reveals the ways in which the processes of borders and bordering are not inert reflections of reality but are deeply connected to different projects of imperial power. Gloria Anzaldúa famously described the U.S.-Mexico border as “una herida abierta [an open wound] where the third world grates against the first and bleeds.” A similar description might apply for the border zone between North and South Korea, a space of impasse that carries along its own histories of empire, war, and gendered violence. At the same time, by writing together and across different heridas abiertas, we approach the “border” not only as a separation, but as a connective tissue. It is, as Anzaldúa wrote, being-in-a-place in which the resulting “Other” is the mirror of oneself—a mirror that does not merely reflect reality but actively shapes the relationship between “subject and object, I and she.” The power of Anzaldúa’s mirror is that there is no separation between the viewer and the viewed. In her recent experimental poetry collection DMZ Colony, Don Mee Choi has similarly approached the border via “mirror words:”

Mirror words defy neocolonial borders, blockades. Mirror words flutter along borders and are often in flight across oceans, even galaxies. Like a butterfly in flight, mirror words reverse neocolonial borders, blockades, and other weapons of empire.

Rather than inert reflections of reality, mirror words force us to read backward and otherwise. The mirror reminds us that the U.S.-Mexico border is not only borderlands, but borderwaters: they are linked to the Pacific and the Atlantic from el Muro in Playas de Tijuana that connects Baja and Alta California to the mouth of the Rio Grande that connects Texas and Tamaulipas.

Diasporic Koreans are one of many peoples who have crossed, dwelled, and inhabited this space. Every day, thousands of workers still wait to cross to el otro lado from Tijuana; Korean migrant history is also inscribed in this daily lived history. The borderlands remember the descendants of the first Korean immigrants, who arrived in Tijuana from the Yucatán peninsula in the 1940s and 1950s and settled on both sides of the border. Their footsteps are traced by Korean migrants today, who transit across the San Diego-Tijuana border for business and pleasure, consumption and sociality: we see them at a Sunday service at Iglesia Coreana en Tijuana (티화나한인교회). The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and now United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) brought South Korean maquiladoras and the global intensification of extractive capitalism, as well as a newer transnational Korean community who build identities that flow between Tijuana, Southern California, and South Korea. These are the social complexities that inhabit the mirror of the borderlands. Only by peering together can we see, as Moraga suggests, glimmers of radical joy: where not just one, or two, but a multiplicity comes together along borders and across oceans.